European Football League Competitiveness

Europeans love football. Even a tiny microstate like San Marino can cobble together a league system with 15 teams from its 35,000 or so inhabitants. We already have European-wide competitions where each country's top teams can face off, and each country is already ranked to show where the best teams come from, but fans will often refer to a less distinct measure of a league's merits: competitiveness. It's an indicator of relative excitement of a league season, while saying zero about the quality, and is typically "felt" more than "measured". I prefer to measure things though (stop giggling, you), so let's formulate a way to let the numbers decide whose football we should be watching.

So what is competitiveness? What makes one league more “competitive” than another? I think it’s fair to say that a league is only competitive if its teams are competitive, and a team is competitive only if it can compete with the other teams in the league (and the other teams in the league can compete with them). And by “compete” we don’t just mean “play a football match”, we mean “play to a level comparable with your opponent to the degree that the result shouldn’t be obvious based on the previous matches”. When we talk of competition in a league we are usually referring to the ability of teams to compete for the main prize, and while that’s important, the whole league needs to be taken into account. Each team in a league plays each other at some point, so if half a league is full of elite teams and the other half are fifth-rate amateurs then half of the matches are foregone conclusions. This gulf will be reflected in the league table, and even though the top half may be really close, the lack of competition between the table halves should be reflected in our calculation.

Let’s imagine a league with only two teams; 1960-era Brazil and an any-era team of Joe clones. Although the football that Brazil play is dazzling world class stuff, with them winning each match 100+ to nil the league cannot be called competitive. If the league instead had two Brazils or two Joe FCs, then it would be highly competitive – equally so in those cases. Of course, one would feature highly skilled athletes at their majestic prime, and the other has to settle for some Brazilians. If we were to allow 1960’s Pelé to jump dimensions to the one with the two Joe FCs wheezing it out, randomly assigning him to a team at the start of each season, then would that league be competitive? Well… no. With the Pelé team winning each match 50-0 every season, the league is essentially as noncompetitive as the Joe FC vs Brazil league. If Pelé plays for Joe FC 2 next season then the league will still be uncompetitive, just with a different team dominating. Players are signed and sold, they’re promoted through the ranks and retire, and managers come and go. Looking at previous league winners is not a good measure of competitiveness, so we’ll develop a measurement of competitiveness based on the results by season. Okay, here goes…

All done! Actually, I’ve split the creation of the statistical index into a (forthcoming) separate article because it’s a tad boring, and you probably want to see the results now. Here’s the lowdown: CCI is the name of our measure. Lower scores means more competitive, higher scores for the more unbalanced leagues. I’ve calculated the competitiveness index for the top league in all 55 European countries with their own national league for the last 5 seasons. The average CCI score for a European league over the last 5 years is 0.3 (well, it’s 0.29946, but that’s close enough).

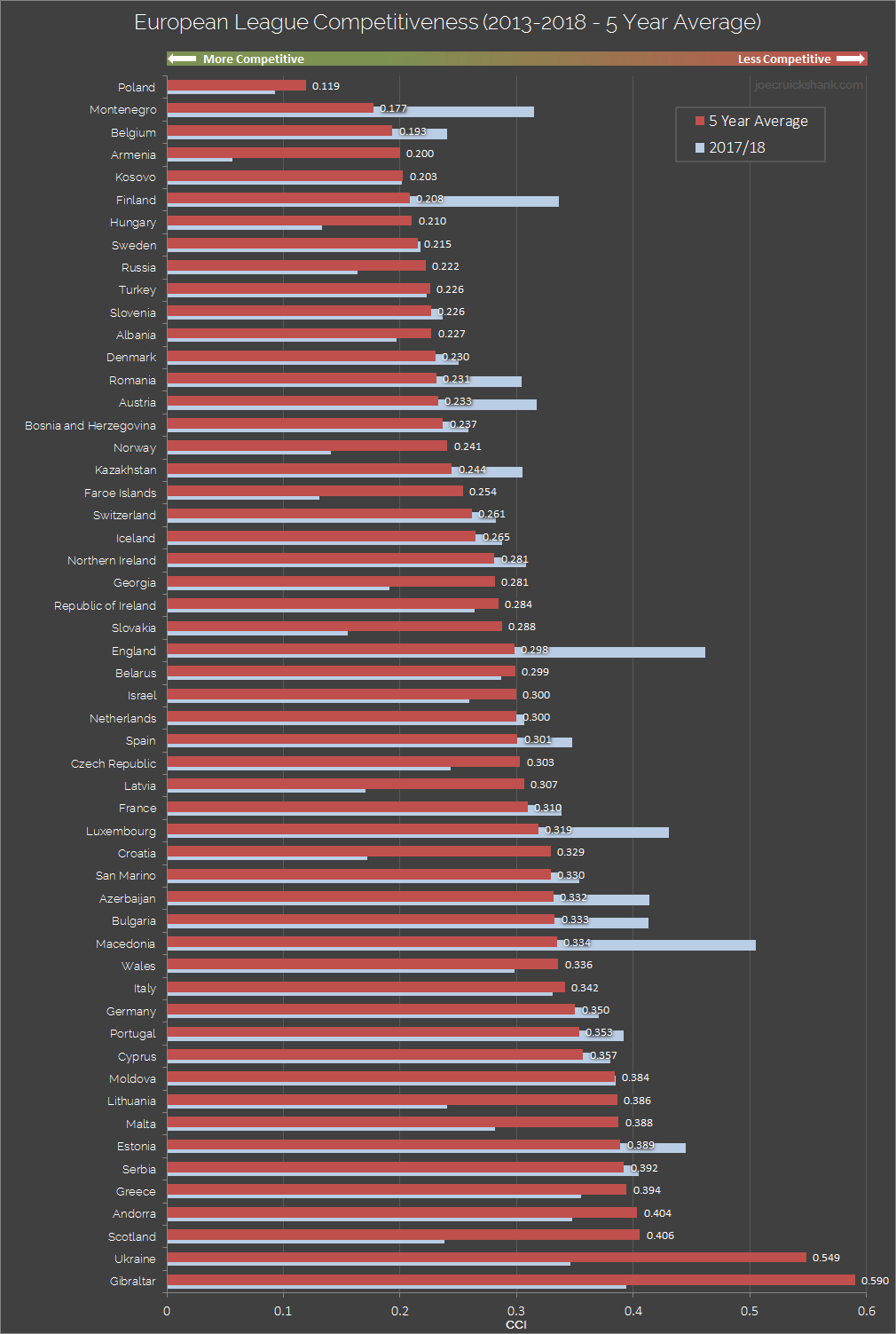

So let’s get started with the results. Here are the CCI scores for all top level leagues in each European country for the 2017/18 season. These are the most recent indicators we have to show league competitiveness:

Lots to take in there. Gibraltar, who normally have Europe’s least competitive top league, have done well to lever themselves away from their 5-year average and up to 47th out of 54. Same applies to Ukraine who are showing at rank 38, way above their 53rd for the 5-year average. As I support a Scottish team I’m delighted to see Scotland up at 16th most competitive. The Scottish league certainly “felt” more competitive last season, so it’s great to see that feeling put into numbers. The first Top 10 league we encounter when travelling down the list is Russia at #7, but there aren’t many of the other big boys at the top. The fans of these smaller leagues up there might not be watching the highest quality of footballers, but the league seasons themselves will be exciting.

Conversely, the English Premier League, which is the most-watched sports league in the world, was the second most uncompetitive top league in Europe last season. It seems to have suffered from the top teams being a class above the rest, and the very top team being a class above that again. Man City finished as champions with a 19 point lead, and no team outside of the top 6 finished the season with a positive goal difference.

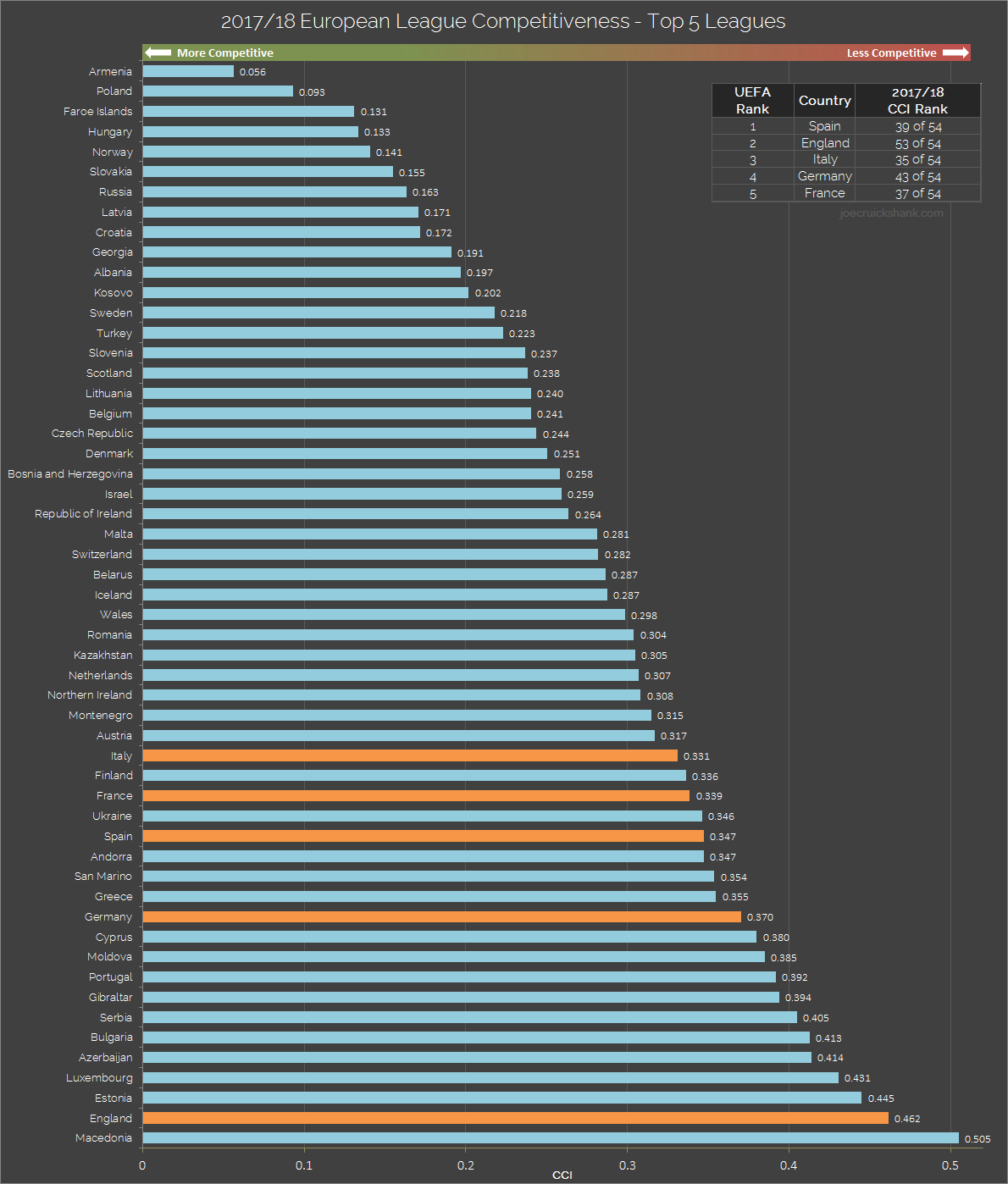

Here’s another chart with the focus on the 5-Year average for a longer term view on league competitiveness:

So if you’re looking for a random league to follow a team in, try Poland. It’s consistently (at least for the last five years) highly competitive, and even the teams that finish bottom of the league still have plenty of wins under their belts. Even though Legia Warsaw have won 5 of the last 6 league titles, it normally runs close. If it simply must be a Top 10 league as determined by UEFA, then Belgium is the one for you.

And for fun (and because it’s the most obvious observation in my view), here’s the 2017/18 results with UEFA’s top 5 European leagues highlighted.

That’s interesting, no? The top 5 ranked leagues in Europe all firmly in the lower half of the chart amongst the least competitive leagues last season. There’s no wider correlation (r = -0.103) between the latest UEFA rank and CCI rank if you take that a bit further though; Russia is 6th in the UEFA rankings with the 7th most competitive league last year. Portugal and Ukraine (ranked 7th and 8th) weren’t particularly competitive (46th and 38th out of 54, respectively), but Belgium and Turkey (9th and 10th) were both above average. Is there a reason for the top leagues becoming more uncompetitive? Is it a money thing, or something else? I’ll leave that one to you to ponder.

To wrap this up, let’s take a quick look at the 5 most competitive league seasons across Europe between 2013 and 2018:

#5 – Ekstraklasa (Poland), 2017/18 (0.0929 CCI)

#4 – Veikkausliiga (Finland), 2015/16 (0.0853 CCI)

#3 – Ekstraklasa (Poland), 2014/15 (0.0758 CCI)

#2 – Prva CFL (Montenegro), 2016/17 (0.0753 CCI)

After 33 matches, three teams are equal on points at the top of the league and have to be separated by head-to-head results. Fourth place is only 2 points off. Budućnost Podgorica are champions despite having lost 10 of their league matches.

#1 – Armenian Premier League, 2017/18 (0.0564 CCI)

Alashkert win the 6 team Armenian Premier League despite winning only 14 of their 30 matches played. Shirak would have ended the season on the same number of points if it wasn’t for some last-game-of-the-season shenanigans. According to Wikipedia:

On 19 May 2018, the Football Federation of Armenia upheld its decision to deduct 12 points from Shirak, and fine the club Seven Million Drams, after it was alleged that Shirak’s sporting director Ararat Harutyunyan had offered Edward Kpodo of FC Banants a bride to fix their upcoming match

Now, I don’t know if “bride” is a “bribe” typo because the source article is in Armenian, but it’s a hell of a story either way. Incidentally, “seven million drams” sounds like an extraordinarily severe punishment to my Scottish ears. Congratulations to the Armenian Premier League though for giving fans their drams’ worth last season.

And for fun, here’s the very bottom of the pile:

#270 – Gibraltar Premier Division, 2014/15 (0.8599 CCI)

Lincoln Red Imps secure their 13th league title in a row with a 16 point lead after a 21 match season. They averaged 3.81 goals per game while conceding an average of 0.57. They scored more goals than the second and third placed teams combined. Nobody was particularly surprised.